How the Quest for Quinine Led to the Creation of Chemotherapy

Will drinking tonic water cure cancer? No, please don’t try that, but the quest to create artificial quinine, the flavoring found in tonic, did lead to the first targeted chemical cures for disease.

Quinine as malaria cure

Gin and tonic photo credit Stefan Schauberger

Quinine in tonic water is a cure for malaria, a mosquito-borne disease. Malaria is tens of thousands of years old and is still one of the world’s most deadly diseases. Historically, it was found throughout the eastern hemisphere before the western hemisphere was colonized by European superpowers, and then it spread throughout the western hemisphere as well. The most notable symptom of malaria is a cycle of fevers and chills that recurs every few days. But the cause of it – microorganisms spread by mosquitoes – was not proven until around 1900.

cinchona bark: the electrolytes of the 1850s

Cinchona officinalis on H. Zell, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In the late 1500s and early 1600s, Jesuit missionaries in South America learned (almost certainly from indigenous inhabitants) of a tree bark that could calm fevers. This “fever tree” is the cinchona tree, native to the high-elevation Andes Mountain areas of Peru, Bolivia, and other countries. Around 1630, the bark was exported to Rome, where malarial fevers were a huge problem in the summers.

It turns out that cinchona bark not only calms the fever that is the symptom of malaria; it can cure the underlying malaria as well. (With modern science we know that the bark prevents reproduction of the malaria parasite in the bloodstream.) With the bark in their bags, European colonizers could now make greater inroads into places like Africa and India, which malaria had made inaccessible.

Powdered cinchona bark was used as a general fever reducer rather than a uniquely malarial one, and it became kind of an all-purpose health-supporting medicine – a tonic. It was found in effervescent tablets sort of like Alka-Seltzer, in cod liver oil pills, and in topical medicines. I call cinchona bark “the electrolytes of the 1850s” as it was used in all sorts of beverages and medicine, whether there was any reason for it to be them or not.

The invention of tonic water

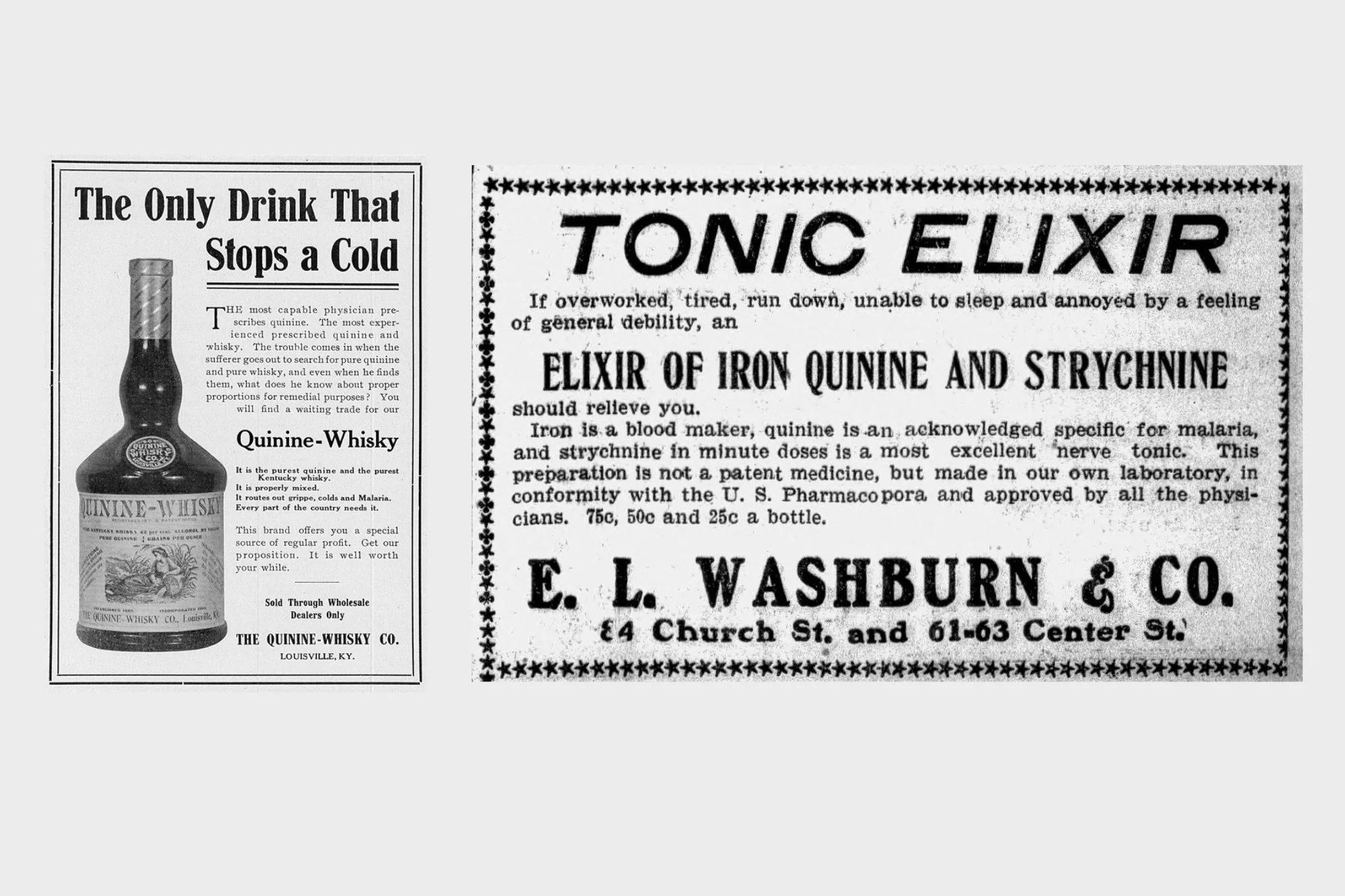

Quinine Whiskey and Tonic Elixir ads

The bitter powdered bark was swallowed with any sort of liquid – wine, beer, sherry, whiskey, lemonade, and eventually carbonated water – to wash it down. Sugar was usually added to balance the bitterness and make it palatable. The fizzy water form became known as tonic water, with the first commercial brand on the market by 1835. (A few decades later, the Gin & Tonic was recorded in print.)

A huge breakthrough came in 1820 when French scientists were able to isolate quinine from the cinchona tree bark. It takes up a lot less space in purified form, so there is less bitter material to swallow. The medicine could be more easily added to beverages and pressed into pill form. But still, all of that quinine had to be isolated from tree bark, and the trees only grew in certain places. Could scientists make synthetic quinine in a lab instead?

From Mauve to Microscopy

William Henry Perkin, via Wikimedia Commons

Chemists in the 1800s were experimenting with coal tar, a chemically complex byproduct of refining gas for streetlamps. A young chemist named William Henry Perkin was given the challenge of creating a synthetic form of quinine from coal tar. He failed at it, but one of his experiments in 1856 produced a bright purple substance.

At the time, purple was an expensive color for fabric dye, traditionally only available to the wealthy. Perkin knew this, so he refined his coal tar dye and went into the fabric dyeing business. Soon he became incredibly wealthy himself in this endeavor. Perkin’s color, called mauveine or mauve, is one of the first synthetic organic pigments, and it had an important impact beyond the fashion industry.

Mauve and other synthetic organic dyes turned out to be incredibly useful as microscopy stains: If you can picture a microscope slide in your head, what color is the sample? Probably purple or pink.

These dyes cling to biological structures in a way that makes them visible, and they helped scientists including Robert Koch and Paul Ehrlich identify microbes responsible for tuberculosis, cholera, and other diseases – only a few decades after the germ theory of disease was proven by Louis Pasteur, Joseph Lister, and Koch.

But now Ehrlich theorized that if the synthetic dyes could stain specific microorganisms so that they were visible, the stains could also be used to target those microorganisms – and kill them. This approach was known as using “magic bullets” to seek out and kill specific foreign bodies in human blood or tissue.

The birth of chemotherapy

Malaria slide

Ehrlich experimented, giving another aniline dye, methylene blue, to malaria patients. This may have been the first instance of a specific disease being cured by a synthetic drug. Ehrlich worked with other aniline dyes on other diseases, including African sleeping sickness. But it was his work using an arsenic-derived compound he called Compound 606 (created on the 606th attempt) to cure syphilis that earned him the honorific “the father of chemotherapy,” the latter defined as the treatment of disease using chemical substances.

Today, the term chemotherapy usually applies to cancer treatment, and using drugs to kill pathogens is known as antimicrobial chemotherapy.

The attempt to create synthetic quinine to combat malaria (and flavor tonic water) led to the creation of a life-saving technique for combating all sorts of diseases. Remember that the next time you sip on a refreshing and understated G&T.