Is the Pousse-Café Making a Comeback?

The Pousse-Café at Archive & Myth in London. Photo credit Archive & Myth

The Pousse-Café is a drink that relatively few living people have tried, yet many millions can identify. The cocktail of liqueurs floating atop each other in any number of layers and color combinations dates to the 1700s when it was a generic term for an after-dinner drink. Specifically, it was an after-coffee drink; the name translates to “push coffee.”

Armin Zimmermann, publisher of the website Bar-Vademecum, wrote what is probably the longest history of the drink in modern times. His 10-part series on the history of the Pousse-Café involves, as he describes, “Ottoman and French coffee house culture, the emergence of the press, the Age of Enlightenment, the emancipation of women, European salon culture, the history of liqueur and sugar, and French and German everyday life.”

We’ll keep it shorter here. The Pousse-Café was also known as the Chasse-Café, a chaser of a liqueur or a spirit to coffee. But the layering technique may have been inspired by another drink.

The Pousse-Past

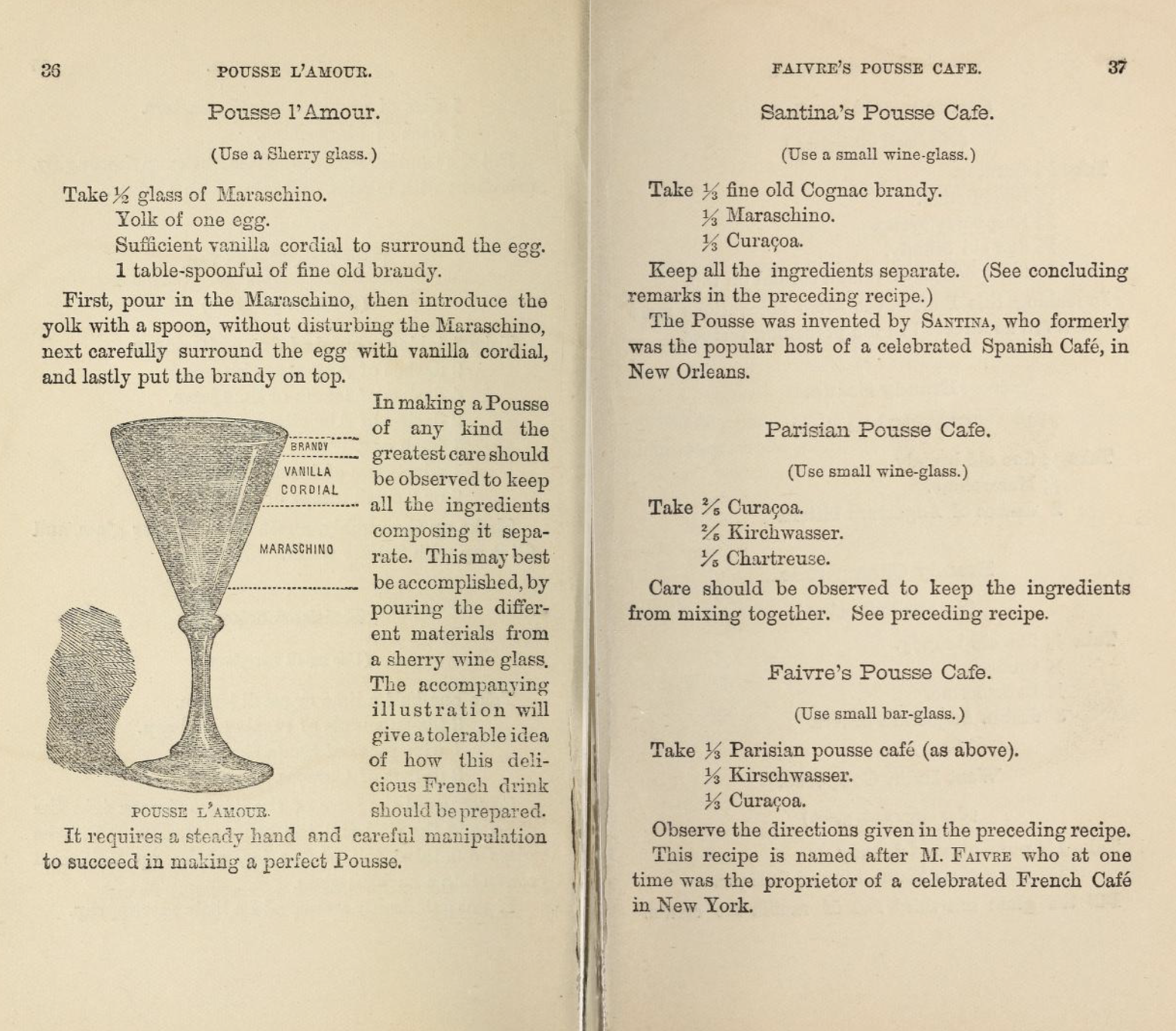

Pousse-Café instructions in an 1887 edition of How to Mix Drinks.

In America, the liqueurs in a Chasse-Café or Pousse-Café may have been mixed together initially, rather than layered. In Jerry Thomas’ How to Mix Drinks, the first bartenders’ guide from 1862, he lists three Pousse-Café recipes. Between them, they include brandy, maraschino, Curaçao, kirschwasser, and Chartreuse as ingredients — but none of the three drinks are specified to be layered. For the Santina’s Pousse-Café, the bartender is instructed to “mix well.”

This could have been an error, though.

Zimmermann dates the first reference to the Pousse-Café as a layered drink to 1851 before the publication of Thomas’ book, and the same three Pousse-Café drinks that are in Jerry Thomas’ book are in Harry Johnson’s New and Improved Bartender’s Manual (1882), which specifies layering. In Harry Johnson’s book, the instructions for the Santinas Pousse-Café are, “attention must be paid to prevent the different liquors from running into each other.” Later editions of Thomas’s book also specify keeping the layers separate.

The layering technique may or may not be borrowed from another drink called the Knickebein, which translates to “knock knees” in German. That drink sounds extremely weird: It is a small liqueur glass usually with yellow Chartreuse on the bottom, an egg yolk added on top of that, and then Goldwasser (an herbal and spiced liqueur with gold flakes floating in the bottle) on top of that. In Harry Johnson’s book, the Knickebein contains vanilla, Bénédictine, kummel, and Angostura bitters. Plus the yolk.

The Knickebein was popular in Germany in the mid-1800s, and came to America with the great influx of German immigrants during that era. Harry Johnson was German, and his book was published in both languages.

Zimmermann suggests that “the custom of layering is probably originally German, but it was refined in the USA.” So, a Pousse-Café might be an egg-free Knickebein. But American bartenders would never be satisfied with two liqueur layers in a drink when four, or six, or twelve are possible! They started adding more and more layers to their Pousse-Cafés — and sometimes setting the top one on fire.

The Pousse-Passé?

The drink fell out of fashion after World War II, according to Zimmermann. Yet images of the drink appeared frequently in cocktail media into the 2000s. By then, the drink had devolved. In the 1980s and 1990s, layered drinks became less associated with dinner and were more aligned with party shots such as the Kamikaze, Slippery Nipple, and Alabama Slammer and novelty shots including the Cement Mixer and Brain Hemorrhage. The surviving layered drinks included the B-52 (with coffee liqueur, Irish cream, and triple sec), and the Tequila Sunrise (tequila, orange juice, and grenadine). Better for the party than the post-coffee digestif.

Bartenders in the 1980s and 1990s would sometimes create other layered shots and give them salacious names. In Gary Regan’s 2003 book The Joy of Mixology, which was published near the beginning of the craft cocktail renaissance, he still includes a layering chart for liqueurs, listing the density of more than 100 liqueurs over five pages. This enabled bartenders to know in advance which liqueurs floated on top of others, so they might be able to layer popular-at-the-time liqueurs like Midori, Galliano, and blue curaçao or coconut cream atop each other.

The Pousse-Today

Jack Sotti’s Pousse-Café. Photo credit Archive & Myth

At the hidden London bar Archive & Myth, not only is a Pousse-Café available, bar director Jack Sotti says it is a “firm favorite” on the menu.

“I've always been fascinated by Pousse-Cafés since I was a baby bartender and always thought that as a mixed drink category they never really saw an appropriate resurgence in the ‘golden age’ of the naughties,” he says. “Perhaps because they are in essence a glass of liqueurs, and at the time ‘serious’ bartenders wanted to move away from the 90s and shooter culture.”

Sotti cites several reasons that the drink could come back, or at least why it’s back at this bar: “I feel like we are having more fun with our drinks as we delve deeper into the culture clash of serious mixology, TikTok trends, and consumer voices being more powerful in our domain.”

In other words, the Pousse-Café is fun and photo-friendly. His version is not merely a throwback to Jerry Thomas’s (or Isaac from The Love Boat’s) time, but a modern interpretation using today’s technology. One ingredient is acid-adjusted, another is centrifuge clarified, and a third is just dyed blue.

The eight layers of the drink in its current incarnation are (from bottom to top) apricot brandy, crème de noyaux, Midori, clarified strawberry and rum, blue curaçao-spiked house vanilla liqueur, acid-adjusted purple coconut rum, Chartreuse, and blanco tequila.

As for the flavors and colors chosen, Sotti says, “It’s a balance between wanting a solid amount of layers for the visual storytelling, and drawing a line in the sand from our B-52 days, and of course creating a delicious drink. Balance plays a part in it but not in the traditional sense, as you are serving a glass of predominantly liqueurs, so instead the focus for me is on complementary flavors, serving temperature, and tempering sweetness with acidity and proof.”

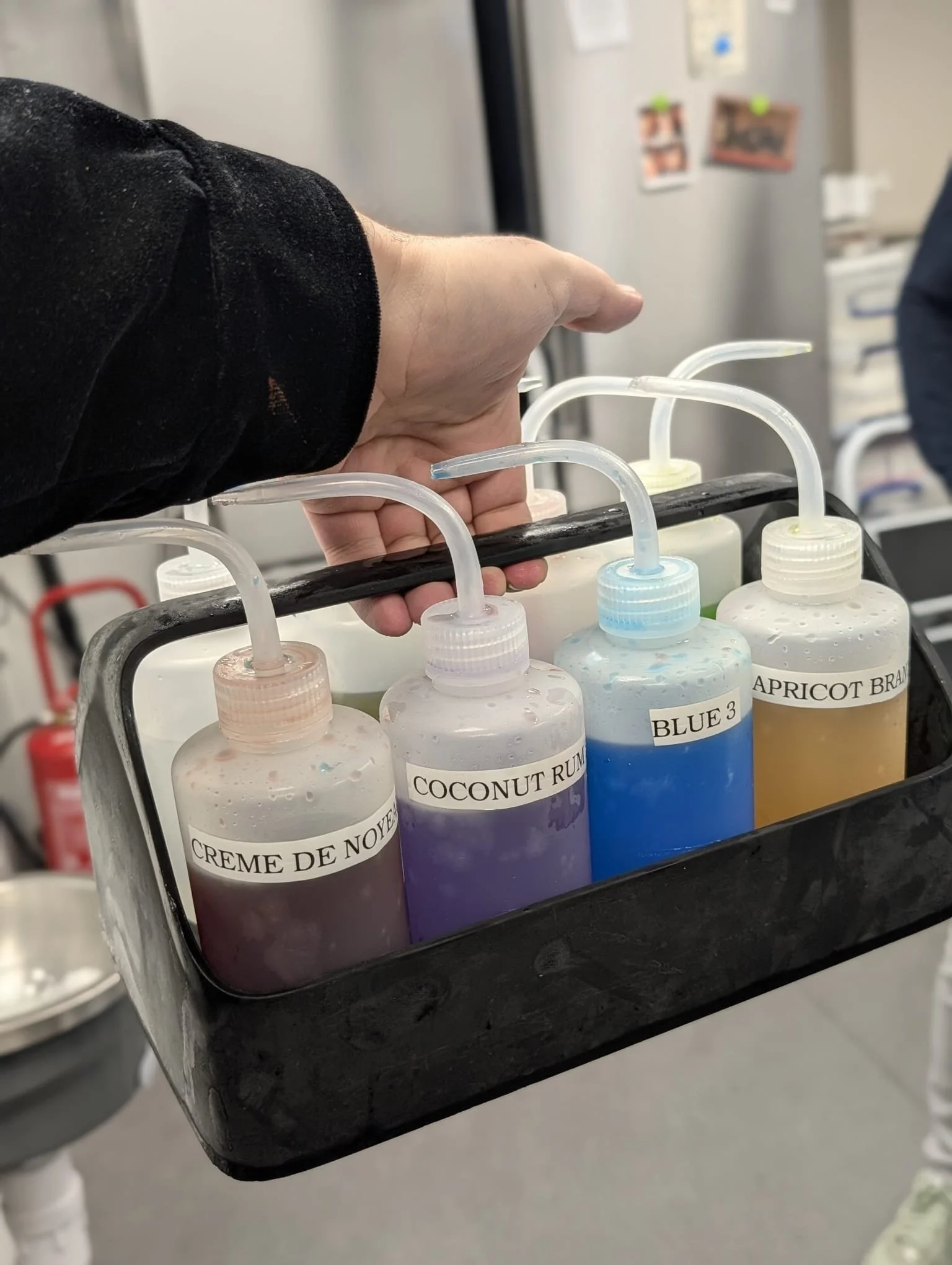

The laboratory wash bottles Sotti uses for layering. Photo credit Archive & Myth

Sotti even figured out a fast and efficient way for bartenders to make the drink with its eight layers in 30 to 40 seconds. He and his team store all eight liqueurs in a single caddy in the freezer, which makes the sweet liqueurs syrupy and slow. This allows them to stack atop each other without having to float them on the back of a bar spoon for each layer as is traditional. They use laboratory wash bottles (that resemble the water bottles that trainers squeeze into boxers’ mouths in classic movies) for their shape, precision, and squeezability.

Harry Johnson instructed people on how to drink the layered Knickebein. The drink was supposed to be consumed in a couple of swallows — first the liqueur off the top, then the egg yolk and Chartreuse together. I asked Sotti how his bartenders instruct drinkers today. His response: “We encourage guests to choose their own adventure, sip through the layers with each one complementing the next, or if they are here to party, down in one, where the flavors meld nicely.”