Boozy Book Reviews: Making Bourbon by Karl Raitz

Making Bourbon by Karl Raitz

After a decade of research, Karl Raitz’s Making Bourbon: A Geographical History of Distilling in Nineteenth-Century Kentucky has finally hit shelves in paperback. At nearly 650 pages including bibliographies and indices, this book is not for the casual Bourbon enthusiast. In fact, this book could be used as a textbook for a distiller’s course as well as suggested reading material for distillery tour guides and brand ambassadors. Whereas books like Michael Veach’s Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey: An American Heritage and Fred Minnick’s Bourbon: The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of an American Whiskey are overviews of the history of America’s native spirit, Raitz’s book is a much deeper dive on many of the same topics.

Making, and mapping, bourbon

Raitz is Professor Emeritus of Geography at the University of Kentucky. He has written and co-written several books, including Bourbon’s Backroads and Kentucky’s Frontier Highway.

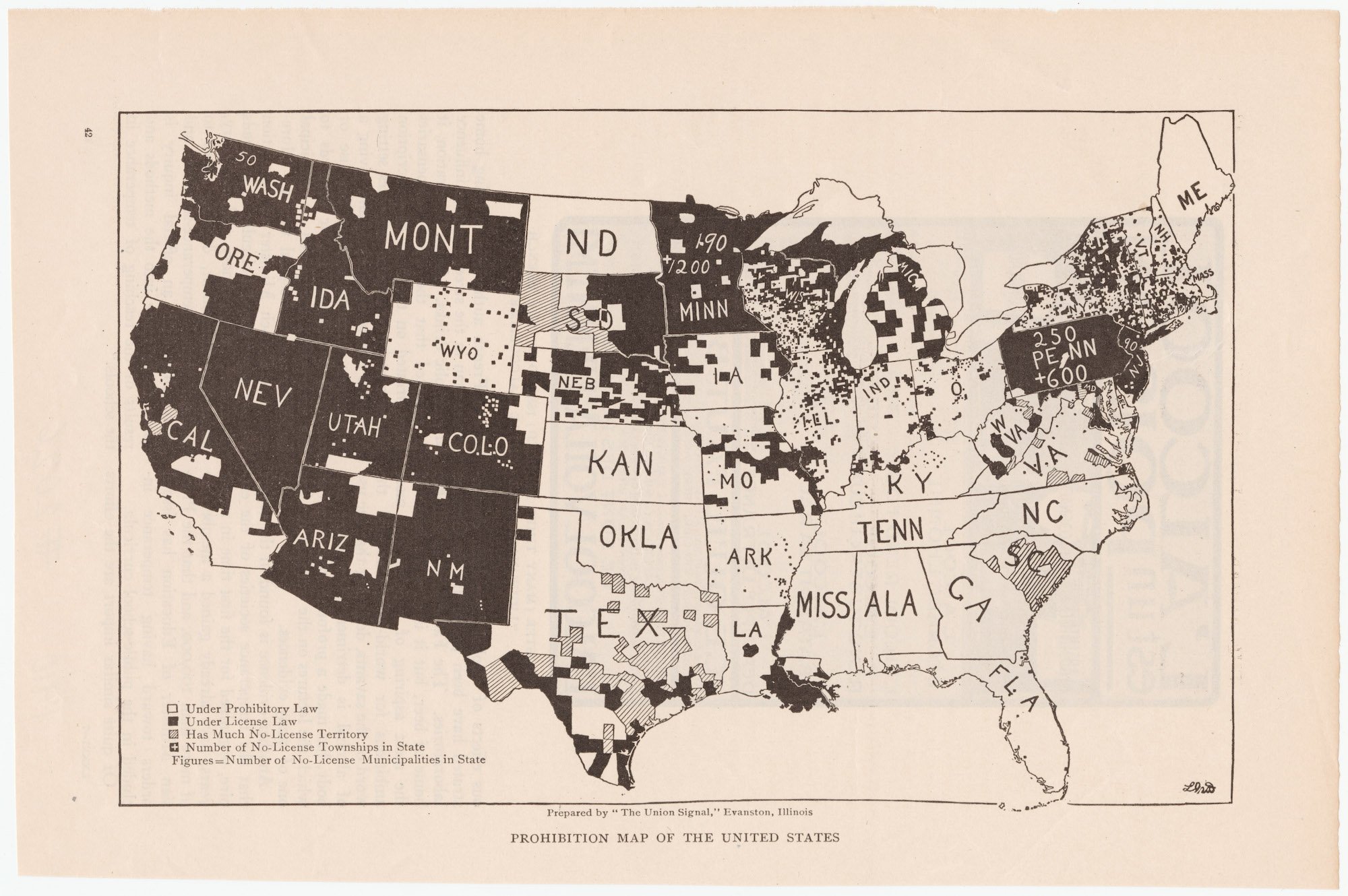

Making Bourbon contains thorough examinations of the history, biology, chemistry, geology, and technology that went into the creation of what today we call Bourbon. There are invaluable charts, tables, and diagrams that show everything from the concentration of Kentucky’s distilleries by county throughout the 1800s to Prohibition maps of the United States before national Prohibition. Of special interest to hardcore Bourbon lovers is a chart of Louisville’s Whiskey Row circa 1909 that shows not only which businesses located their offices on Whiskey Row but also the order in which they were situated.

Prohibition map courtesy of Cornell University – PJ Mode Collection of Persuasive Cartography.

A historical deep dive

Of particular interest to craft distillers is the section on corn history in chapter four. There’s a wealth of information in here that craft distillers could mine for ideas on finding or reviving new types of heritage corn that have traditionally been used in whiskey making and for other purposes. There’s great information in here about why the Ohio River Valley region excelled in growing corn on the frontier days and what it meant for Bourbon produced in this region (more starch in the corn, for starters).

There’s also a deep dive into frontier and pre-industrial foodways and later into post-industrial foodways as they transitioned into manufacturing ecosystems. Tracing the ties between distilleries and farms is clear and obvious even today, but those foodways and manufacturing ecosystems have historically also included things like feed lots, which produced hides, which fed into tanneries, which fed into shoe, belt, and harness production. Especially for the smaller producers who are trying to showcase the farmer-distiller model of production, this information could be especially valuable when designing visitor experiences.

In addition to these examinations of historical economies, this book digs into things like the epistemological questions of how we know what we know about these histories. On the fourth page of the book, Raitz digs into this and positions it in relation to how technological changes would have taken place in early distilling.

Old Crow Distillery by Matt Shiffler Photography is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Facts, tidbits, and distilling

There are a few facts that are in dispute in this book. James Crow was likely not a doctor, which Veach discusses in his book. Even on the first page of chapter one, the premise of how distillers came to Kentucky — the myth of escaping the national whiskey tax during the Whiskey Rebellion — has been repeatedly proven historically false for a number of reasons, not the least of which is that Kentucky was part of the United States at the time and subject to Federal law and there were already people living and distilling here at that time. Even Evan Williams had already started distilling in Louisville a decade or more before the Whiskey Rebellion took place.

There are plenty of interesting tidbits throughout this book, including that fermentation is a form of combustion, something almost no one talks about on a standard distillery tour. There is discussion about yeast and how cultivating proprietary yeast is a time-honored tradition in historic distilling. One of the best quotes in the book addresses something I teach about all the time in the context of America’s distilling history: “Great inventions are never, and great discoveries are seldom, the work of one mind.” (Robert Henry Thurston). Whenever someone claims that this person was the first distiller or that person invented a new process, it’s hard to pin down the actual truth because major discoveries build on humanity’s collective knowledge, even in distilling.

Making Bourbon builds on volumes of available data to help explain how Kentucky Bourbon got here. It’s a great reference for anyone researching even small parts of distilling history because of the detailed index. Part II is dedicated to just two distilleries: Henry McKenna’s distillery and James Stone’s Elkhorn Distillery. The contributions made by these two early distillers have a lot to do with Kentucky Bourbon’s enduring success.

The final section deals with branding and the future of the distilling industry. This book is almost three books in one: the first section is for those wanting a technical understanding of how Bourbon is made, the second section is for those wanting to know the history of how the Kentucky Bourbon industry was built and has lasted, and the third section is a primer for brand builders and spirits marketers.

We recently caught up with Karl Raitz to learn more about the work that went into producing this book.

How long did the research process for this book take? What was it like?

Author Karl Raitz

The research that provided the foundation for Making Bourbon: A Geographical History of Distilling in Nineteenth-Century Kentucky took the better part of a decade. Library archival work, primarily in collections of historic family papers, newspapers, and other printed materials constituted the bulk of that work. Some materials were available in hard copy originals, other sources were on microfilm. I also conducted a number of field investigations looking for historic distillery sites and other structures such as distiller’s homes, trying to locate old roads and river port landings, cemeteries, etc. While the field work focused on Kentucky and included distilleries currently in operation, it also included trips to Peoria, Illinois, Cincinnati, Ohio, and Ireland where I visited several historic distilleries and the Draperstown area in Northern Ireland, Henry McKenna’s home town.

What was your biggest surprise when researching this book?

The biggest surprise was the realization of how technically and financially difficult it was to make the transition from traditional craft distilling to industrial distilling. Distillers had to recognize the value of new technology, adopt the equipment required, learn how to operate it properly and safely, and then cope with the production and marketing of their product in a way that yielded a profit while also paying all the debts they had incurred in the transition. And, they had to manage all this while under the heavy hand of federal taxation policies that were increasingly financially burdensome and placed their businesses under the control of government political appointees.

What was your favorite topic to research?

I can’t say that I had a favorite topic or subtopic because I found it all of great interest. Whether it be the new inventions that contributed to increased production, the unexpected consequences that resulted—such as the large volumes of spent grains or “slop” that required disposal—the potential hazards of explosions and fire, or the competition between distillers for access to high quality grains, it all came together to portray a interlinking set of interrelationships of unexpected complexity. And dealing with all this was especially difficult when one considers those operations within the context of their day and such basic difficulties as transportation and communication in an era of poor roads and slow mail. Of special interest to me were the extensive records available for James Stone’s Elkhorn Distillery in Scott County and Henry McKenna’s distillery in Nelson County. There was sufficient information on these two operations to reveal in considerable detail how they operated and, in the end, why one failed and went out of business and the other enjoyed long term success such that the brand name is still in production today. Their story comprises four extensive chapters in Part II of the book.

Why should people pick up your book and read it?

Making Bourbon is a long book and will likely require dedicated reading, but it will reward that effort by providing interesting information. As philosopher Theodore Schatzki has said about the book, it is “the most comprehensive and myth-busting available on the Kentucky bourbon business”. (Schatzki’s book is entitled Social Change in a Material World).