Your Sake Adventure Begins Here

You’ve maybe seen a fictional group of samurai drinking it from tiny cups in a movie. Perhaps you’ve come across the large colourful bottles in your local liquor store. But what is it? It's Japanese sake and, sadly, most people outside Japan know very little about it.

It’s an intimidating category in the drinks industry. With a history as rich and large as wine, set in a unique culture and told in an unknown language, Japan’s rice wine is a hard topic to tackle. Hopefully this helps. Not everything about sake can be covered in one article, as that would require books upon books. However, presenting the knowledge needed to delve into the category, is a great start. Here are some basics about Japanese sake to get your journey started.

Sake Production 101

Let’s start with a common misconception: While in the West it refers to rice wine, the term "sake" (酒) in Japanese is used for all types of alcohol. Sake can be beer, whisky, wine. What we call "sake" is called "nihonshu" in Japan. It's time for a crash course on how sake is made. The most important ingredient used is, you guessed it, rice. Over 70 varieties are used to produce the many different types of sake out there.

After the rice is selected, it is "polished", which refers to a method that removes the outer part of the rice grain. The exposed core, which contains the starch, can now be easily fermented. The extent to which the rice is polished greatly determines the quality of the final product. The higher the polishing percentage, the purer the sake. Polished to, say, 60 per cent suggests that the remaining 40 per cent has been taken away.

After polishing, when the rice has been washed and steamed, part of it is spread out on tables in a humid, temperature-controlled room. Koji mould spores are blended into the rice, which helps with the extraction of fermentable sugars. Following this, yeast and water are added to the mixture. Over the next four days, now in a larger tank, extra rice, koji, and water are continuously added into the fermented mixture. This happens in 3 stages to allow the yeast to keep up with the added ingredients. The mash (known as moromi) is then left to ferment for 2 to 3 weeks.

When the time is right the resulting mixture is pressed, allowing the clear liquid to run out. The sake is then typically charcoal filtered and pasteurized, done by running it through a pipe surrounded by hot water. Finally, the wine is usually left to age for several months, which balances and mellows out the final flavours.

Methods and equipment have, of course, progressed and developed over the years. The many different styles of sake see different steps in production. This all depends on the brewery’s toji, the master brewer.

Drinking In Style

Will a basic understanding on how it’s made, let’s look at styles and how to drink the mysterious rice wine.

Junmai - This is the best style to start with, known as the “purest” type of sake made using nothing but rice, water, yeast, and koji. No additives whatsoever. Look at it as the Scotch whisky of the sake world, as it were.

Try the Tenzan Shichida Junmai 75 sake for a pure expression.

Honjozo - This is another major category, which must be polished to at least 70 per cent and includes a small amount of brewer’s alcohol, to mellow the wine out, making it smoother and lighter on the palate.

The Gekkeikan Nouvelle Tokubetsu Honjozo sake perfectly introduces the style, and all the light, fruity, refreshing notes that go with it.

Ginjo & Daiginjo - These are premium categories with rice that must be polished to at least 60 and 50 per cent, respectively. Labelled Ginjo or Daiginjo means it has brewer’s alcohol added, if the word Junmai is attached, no additives are added.

The Dassai 50 sake by Asahi-Shuzo is a well respected offering under the Junmai Daiginjo premium category, and provides a great, affordable introduction to the style. Or to try something special and unusual, Hakkaisan produces a very well balanced Junmai Ginjo and a special Snow Aged Junmai Ginjo, aged for 3 years in a room, known as "Yukimuro", insulated by snow.

Namazake - The above make up the most major categories. Another popular, yet lesser known type is Namazake, which is a hazy, unpasteurized sake. These expressions usually deliver a welcomed nuttiness and earthy character.

The Mountain Stream Junmai Bodaimoto is unpasteurized Namazake, great for an introduction of this style of wine, before pasteurization takes place.

Hot or Cold?

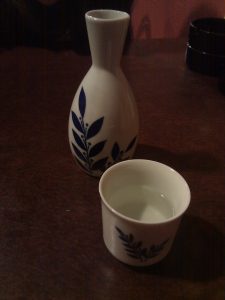

Sake is usually consumed chilled or hot (atsukan). Winter calls for hot sake, while the warmer months bring the chilled serve. Many expressions have suggested serving temperatures. Some are better warm, and others cold. Typically, though, higher quality sake isn’t served hot as the heat strips away the sake’s character. The same way commercial beer is served ice cold, cheaper sake is often served hot to mask the lack of flavour.

Once you’ve tried the expressions plain, be sure to experiment with cocktails. You could even try some sparkling sake. Time to head to your local bar or liquor store and try some sake. Pair it with some Japanese food for the best results!