The Bar That Birthed America

Despite our disastrous flirtation with Prohibition, much of the character of the United States, in the early days of its life as first a colony of Great Britain and later as a newly minted independent nation, was hammered out by men raising tankards of booze in taverns and public houses. In fact, most of the Founding Fathers and notables of the American Revolution were brewers, distillers, tavern owners, or rum runners. Some were all of the above. The Sons of Liberty devised the Boston Tea Party in Boston’s Green Dragon Tavern (and decided to toss tea instead of the much more valuable rum, because they liked the rum). Meetings of rebels, and later the nascent American congress, took place in a tavern. And when, at the end of the war, George Washington returned triumphantly to New York City, he chose to make his final address to his troops at a tavern.

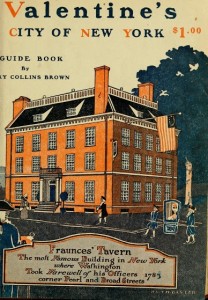

That tavern, Fraunces, is still standing, a modest yet instantly noticeable tan brick Federal style building surrounded by the towering steel and glass that defines modern lower Manhattan.

Fraunces began life as a residence traded amongst some of New York’s most powerful families, the kind who still have streets and neighborhoods named after them. The original building was constructed in 1671 by New York Mayor Stephanus van Cortlandt. When the mayor retired to an estate further up the Hudson River, he gave the property to his son-in-law, Etienne DeLancey. He, in turn sold the mansion in 1762 to Samuel Fraunces, who immediately converted it from a residence into a tavern called The Queen’s Head.

It didn’t take long for Fraunces’ new bar to become the headquarters for growing American discontent. The Sons of Liberty met at the tavern, swapping plans over plentiful drinks (there were few teetotalers among them, and the alcohol consumption of the average Colonial American would stagger the average modern drinker). New York and the City of Brooklyn were eventually lost to the British and remained British throughout the duration of the American Revolution. When the British surrendered however, there was no better symbol for American victory than Washington’s triumphant return to New York.

British troops evacuated New York on Nov. 25th, 1783. Washington arrived on the rural outskirts of New York (around what is now the intersection of Bowery and Bayard) that same day. He and his retinue paused for pints and planning before their triumphant return to the city while some 800 troops and camp following politicians gathered outside a tavern called the Bull’s Head. Opened sometime during the 1750s, the Bull’s Head Tavern was one of the last stops before entering the hustle and bustle of the city proper. A place to “hear tales of travelers, watch the coaches and envy the more pretentious country gentlemen in Castor hat, cherry-derry jackets and doeskin breeches,” as it was described by another Washington (Irving).

On December 4th, Washington’s procession rode through the streets of New York City amid throngs of cheering, newly free Americans. The trail ended at the tavern once called Queen’s Head, now known as Fraunces, where in the establishment’s Long Room, Washington bade farewell to the soldiers who had served under him during the hardships of the war. “With a heart full of love and gratitude, I now take leave of you. I most devoutly wish that your latter days may be as prosperous and happy as your former ones have been glorious and honorable."

George didn’t travel very far from Fraunces Tavern after that. The seat of American government remained in New York, and The Departments of Foreign Affairs, Finance and War had their offices at Fraunces Tavern, along with a portion of the Continental Congress. Using a tavern as a seat of government was an age-old tradition, after all. Even after the seat of US government was moved to Washington, D.C., Fraunces Tavern endured.

Like just about everything in the late 1700s and early 1800s, it burned down and was rebuilt several times. In 1900, the owners of the building decided to tear it down (Federal Hall had been demolished almost a century earlier, in 1812). There was no such thing as the landmarks system we have now, but the Daughters of the American Revolution worked with the city to prevent the historic building from being knocked down and turned into a parking lot. It was temporarily designated as a park, until in 1904 the Sons of the Revolution In the State of New York raised enough funds to purchase the property.

In the 1970s, it was the site of a different sort of revolution, when on January 24, 1975, the building was bombed by the Puerto Rican nationalist group "Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional Puertorriqueña” in retaliation for the deaths of three people in a restaurant in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico two weeks earlier, which Fuerzas Armadas referred to as “a CIA ordered bomb.” Four people were killed in the bombing of Fraunces Tavern and another 50 wounded.

Although the constant rebuilding and remodeling left little in the way of original materials, Fraunces as it stands today is a faithful reconstruction of what it probably looked like (albeit with a few extra floors) when Washington and his troops sat down for their turtle feast in 1783. A museum dedicated to the history of Colonial era New York and the role Faunces played in the Revolution is housed in the building, as well as a restaurant and, this being a tavern still after all, an excellent tap room serving Porterhouse Brewing Company craft beers (among others) and a comfortable, nicely-stocked whiskey bar called The Dingle.

If you happen to find yourself in Lower Manhattan (in perhaps from the rough rural farmland above Canal Street), consider the turtle feast optional. But do drop by Fraunces Tavern and raise a tankard or two to Washington, to bars and taverns, and to the rabble-rousing hellraisers who flock to them when its time to plot the overthrow of a government.